A century ago, India got its rare, and strange, Rs 2.5 note

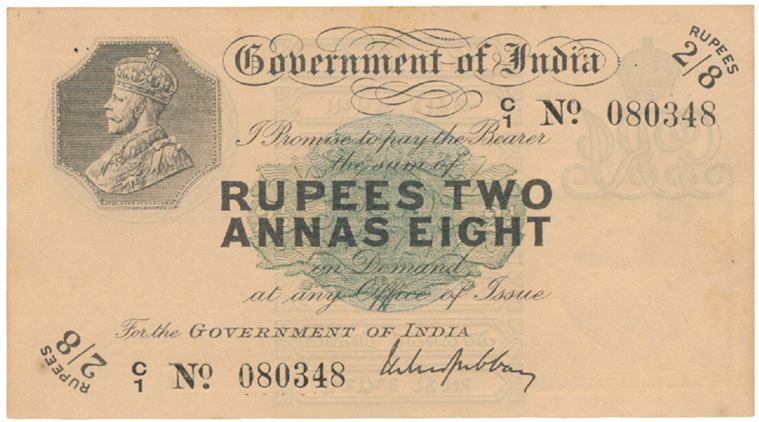

On January 2, 1918, the British government of India released an exotic bank note of Rupees Two and Annas Eight, or two and a half rupees.

While silver coins of a smaller denomination (the silver 1/2 Rupee, 1/4 Rupee and 2 annas) were discontinued and replaced with cupro-nickel coins, the British India government also issued Rupee 1 notes in November 1917 and shortly after that, Rupee 2 ½ notes on January 2, 1918.

On January 2, 1918, the British government of India released an exotic bank note of Rupees Two and Annas Eight, or two and a half rupees, as one rupee in British India was divided into 16 annas — a term adopted from the pre-British Muslim monetary system. This unique, fractional Rupee currency issue completes a centennial today.

According to bank notes enthusiast Dr Suraj Karan Rathi the currency was printed in England on white, handmade paper and bore the emblem of Emperor George V and the signature of erstwhile British finance secretary M M S Gubbay. The currency marked by seven prefix code variations denoting its circle — A (Cawnpore/Kanpur), B (Bombay), C (Calcutta), K (Karachi), L (Lahore), M (Madras) and R (Rangoon) — which was a vestige of earlier years when currency notes used to be legally encashable only within their circle areas. The value of the currency (‘adhai rupya’) was stated at the back in eight Indian languages. Significantly, the value of Rs 2.5 was the exact equivalent $1 at the time.

During World War I years (1914-1918), the prices of silver soared as demand for the metal in the war time grew. So much so that the intrinsic value of the silver rupees, which is the value of the silver in the coin, was perceived as greater than the actual value of the coin. People indulged in speculation and began hoarding coins for their own gains, leading to a shortage of silver for minting sufficient coins for meeting public demand.

Panic of World War I

In one of the first acts of aggression in World War I, when the German warship SMS Emden came to the Madras shore and opened fire at storage tanks of the British-owned Burmah Oil Company on September 22, 1914, the act generated a panic among Indians who lost faith in government issued currency notes. Paper money, at the time, was treated more pragmatically like a legal tender to be encashed for silver coin Rupees by India’s low income classes.

To obviate distrust, the government treasuries were at first forced to cash the paper money for silver coin rupees, but soon reached a point where convertibility was no longer feasible due to insufficient silver reserves. Seeking the help of the government of the United States, the British Indian government was able to replenish silver from the bullions purchased from the US — created out of melted silver dollars. As the late numismatist P L Gupta explained in his seminal volume Indian Paper Money, that year mints in India produced over 260 million silver rupees. And yet they were unable to meet public demand. It became impossible for the government to keep issuing silver coins and imperative for them to conserve and economise the use of the metal.

As a result, the process of withdrawing silver coins from circulation began. While the silver coins of a smaller denomination (the silver 1/2 Rupee, 1/4 Rupee and 2 annas) were discontinued and replaced with cupro-nickel coins, the British India government also issued Rupee 1 notes in November 1917 and shortly after that, Rupee 2 ½ notes. Before this, Rs 5 were the lowest currency notes in circulation.

Referred to in official communication as rupees 2/8, the reason for this odd denomination was noted in Letter No. 139 of 1917 of Government of India’s Finance Department: “We cannot look for immediate acceptance of such notes in any large quantities, and we consider that 2/8 note, which would introduce a fresh denomination intermediate between the available one Rupee coin and a Five Rupees note which ordinarily hold out better chance of success” (As recorded in Kishore Jhunjhunwala and Rezwan Razack’s Reversed Standard Reference Guide to Indian Paper Money). In the beginning, Gupta writes, the currency notes did not evoke trust among the people, and were used in the market only at a discount of 15 – 19 per cent. They were only accepted at par after about a year or two passed since they were introduced into circulation.

Short-lived denomination

A collector’s rare delight, a surviving currency issue of 2 ½ denomination was auctioned for a hammer price Rs 6,40,000 against an estimated Rs 2,50,000-3,00,000 in Mumbai’s Todywalla auctions on December 2, 2015. “It was printed when India was experimenting with shifting from the rupee-anna denomination to the dollar. So they came out with this one, which is equivalent to one dollar. In the public space it did not work, so circulation had to be withdrawn, which is why the note is very rare indeed,” Farokh Todywalla, the founder of Todywalla auctions, told The Hindu.

The currency notes of both Re 1 and Rs 2 ½ were withdrawn from circulation on January 1, 1926 due to cost-benefit considerations, as the Government of India once more reverted to coins — not wholly silver this time. While One Rupee currency notes returned in 1940 (during World War II), another currency note of fractional denomination like 2 ½ was never issued

→

→

0 comments:

Post a Comment