What ails India’s approach to Universal Health Coverage

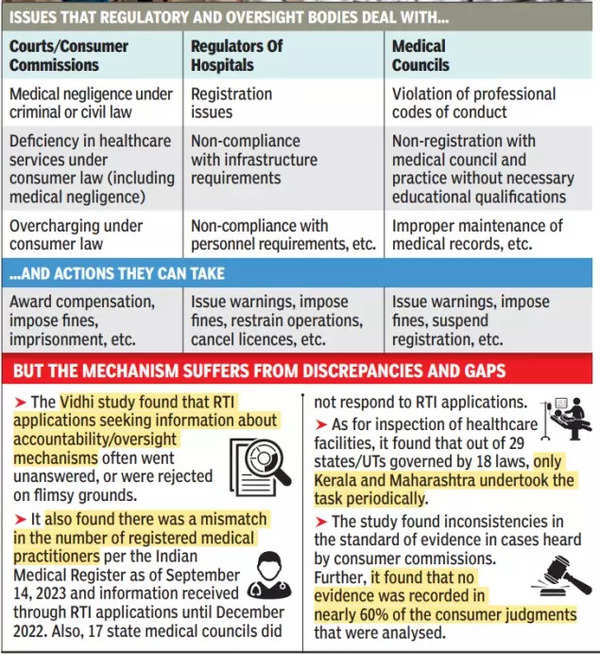

Healthcare providers in India are held accountable by the state through four primary mechanisms – courts, consumer fora, medical councils that regulatehealthcare professionals, and regulators of clinical establishments. A study of these mechanisms that analyses around 128 RTI responses, 440 judgments, and 50 laws and regulations reveals a worrying lack of clarity as to how institutions analyse and decide matters, causing distress to patients and doctors alike.

The authorities regulating doctors and hospitals are almost entirely hidden from public scrutiny, partly due to poor record-keeping. For instance, the Indian Medical Register, which tracks the number of active registered medical practitioners, is not updated properly. Further, although four years have passed since the National Medical Commission was established, it has yet to set up the National Medical Register. Similarly, there is no central record of all registered and operational healthcare facilities in the country.

According to Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an ideal model for inspection should facilitate compliance before imposing strict penalties, reserving the latter for serious breaches. Under the current hospital regulation framework, inspections are rare and often lead to knee-jerk regulatory sanctions like the cancellation of licences without sufficient notice. The absence of a model for supportive supervision sometimes leads to the sudden closure of hospitals in an already overburdened healthcare system.

State medical councils (SMCs) can sanction doctors for violating codes of conduct, but they can also deal with ‘professional misconduct’ beyond these codes. Doctors are thus often unsure about what may constitute a violation. Moreover, SMCs tend to issue warnings that are neither reflected in professional records nor followed up with stringent action in case of non-compliance. Only the Karnataka Medical Council publicly lists doctors who have been held liable for misconduct. On the other hand, several councils refused to provide details of disciplinary proceedings sought through RTI applications.

When it comes to medical negligence, judgments over the last three decades have applied inconsistent standards of evidence. In fact, they often fail to clarify what evidence was relied upon, and nearly 60% of decisions by consumer commissions do not mention any medical evidence at all. In some cases, commissions not only insisted on independent expert opinion but also rejected claims as complainants failed to arrange for a medical expert for themselves. In other cases with similar claims, the commissions arranged for experts on their own. The parameters for attributing liability are thus unclear for both healthcare providers and patients, leaving them confused as to how they should strengthen their claims or defence. Uncertainty and inconsistency in evidentiary standards also present a challenge in criminal proceedings. Similarly, compensation amounts are calculated without applying formulae uniformly.

These unclear, inconsistent and opaque regulatory mechanisms do little to resolve patient grievances and also fail to provide relief to doctors facing the spectre of undue harassment. Building adequate capacity in these mechanisms is necessary to improve regulation. That would include developing uniform standards for quality and liability, empowering regulators to make constructive recommendations, and allocating resources for data management. In a larger sense, we need to rethink regulation as a tool for improving health coverage in India, rather than a mode of imposing exemplary punishments in sporadic cases.

→

→

0 comments:

Post a Comment